June 16, 2025

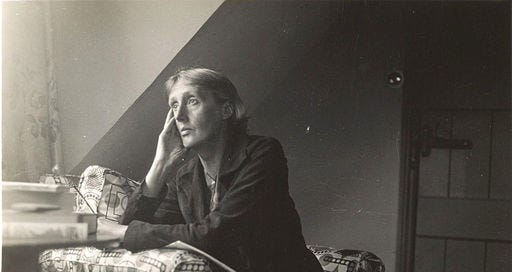

It gradually and only recently dawned on me that Virginia Woolf and I have been observing current affairs similarly, albeit on different astral planes, given that she’s dead. For the past six months, I’ve been re-reading the five volumes of her diaries, which Granta reissued in 2023.1 I first read the original editions in the 1980s. I was struck as forcefully by the flash of her penetrating insights now as I was then, although her crude racism and class snobbery still make me gasp. I carried the thick tomes with me to Hudson, Paris, Hudson again, and New Orleans. I’ll take the fifth and final volume with me on the ride back to California in a week.

I got as far the early 1930s about a month ago. It was then that I realized VW had something to say about our world today that I hadn’t known to look for.

In the entries for 1931, ‘32, and ‘33, it was hard to miss the parallels between the events she observed and the ones I see now. She knew a lot about politics and the rise of fascism, more, in fact, than most of the British public in her time. She had the advantage of knowing and talking regularly with politicians, policy makers, journalists, and aristocrats, as well as with artists and writers. Her husband, Leonard Woolf, born into a secular Jewish family, was a prominent member of the Labour Party. He and Virginia owned their own publishing house, the Hogarth Press. He served as long-time literary editor of The New Statesman & Nation, and was the author of several books, including the 1935 essay, “Quack, Quack,” an anti-fascist polemic. Virginia and Leonard were the epicenter of the Bloombury coterie. Their friendships and Leonard’s work in support of the Labour Party gave her a privileged view of the developments leading to the outbreak of war in 1939.

Starting in Volume 4, which which covers 1931 to 1935, Virginia makes mention of news from Germany with increasing frequency. The first appearance of Nazi Germany in the diary is alarming not only for the events she relates but also for the evident agitation and speed with which she wrote. On Monday, 2 July 1934, news of the Night of Long Knives reached Britain. Her friend, the poet Osbert Sitwell telephoned her.2

Rung up by Osbert Sitwell just now. After hopping & jumping about publishers, Holroyd Reece, lunches dinners & teas, he comes out with, “And can’t anything be done about this monstrous affair in Germany?” “one of the few public acts” I said “that makes one miserable”. Then trying, how ineffectively, to express the sensation [of] sitting here & reading, like an act in a play, how Hitler flew to Munich & killed this that & the other man & woman in Germany yesterday. A fine hot summers day here & we took Philip Babs & 3 children to the Zoo. Meanwhile these brutal bullies go about in hoods & masks, like little boys dressed up, acting this idiotic, meaningless, brutal, bloody, pandemonium. In they come while Herr so & so is at lunch: iron boots, they say, grating on the parquet, kill him; & his wife who rushes to the door to prevent them. It is like watching the baboon at the Zoo; only he sucks a paper in which ice has been wrapped, & they fire with revolvers. And here we sit, Osbert I &c, remarking this is inconceivable. […] And for the first time I read articles with rage, to find him called a real leader. (4: 296)

Virginia’s fury as she writes this account, paying little attention clarity and grammar, spills of the page. Her anger at the way the press soft-pedaled the menace that Hitler represented doesn’t feel all that different from mine when reading the headlines of The New York Times during the last presidential campaign.

Later in the same month, she listened to Leonard and friends — T.S. Eliot, Desmond MacCarthy, among others — argue over dinner about the way the British government ought to handle relations with the Nazi regime. Should the government focus on keeping the peace with Hitler or should it stand up to him? Virginia describes the conversation as heated before admitting her mind was caught up in solving composition problems in the novel she was writing (which she would eventually call The Years). The threat does not yet feel close.

Six months later, in January 1935, Virginia recorded that she received an invitation to contribute to an anti-fascist exhibition sponsored by the Cambridge Anti-War Council. She objected to the lack of attention in the planned exhibition to “the woman question.” A month later, she writes, “And here I am plagued by the sudden wish to write an Anti-fascist Pamphlet,” which she and Leonard discuss in great detail. The pamphlet idea was abandoned. The possibility of war was still remote.

Here in England we haven’t even bought our gas masks. Nobody takes it seriously. But having seen this mad dog [Hitler], the thin rigid Englishmen [i.e. members of Parliament and diplomats in the Foreign Office] are really afraid. And if we have only nice public schoolboys like W. to guide us, there is some reason I suppose to expect that Oxford Street will be flooded with poison gas one of these days. (4: 402)

This sentiment, too, feels familiar. Her frustration that her elected leaders were too frightened to mount a resistance to a very real threat feels a lot like my indignation at the lack of leadership in Congress.

Then, in May, 1935, rather astonishingly, Virginia and Leonard decide to take a car trip through the Netherlands, across Germany, and then into Austria and Italy, before heading north through France, and back to England. Visiting Germany seems risky enough, but sight-seeing in Rome while Mussolini was amassing troops preparatory to invading Ethiopia six months later strikes me as reckless. Were they underestimating Nazis and fascist malevolence? Were the reports of violence they received a little too abstract? Or did they go in the spirit of journalists and witnesses in order to see for themselves? She doesn’t explain their decision. Nevertheless, they set off.

When they reached the frontier between Holland and Germany, Virginia waited in the car while Leonard entered the customs office to present their documents. He remained in there longer than Virginia thought reasonable. She started to worry. A car with a swastika in the back window drove past her while she waited. Finally, Leonard emerged from the office, accompanied by customs officers. They walked Leonard to the car where Virginia waited. One of them, a “grim man” laughed at Leonard’s small pet marmoset, Mitzi. That the Woolfs brought their pet monkey on a car trip through Germany in 1935 might be further proof that they were not yet taking Nazis seriously. But they started to on this trip.

We become obsequious — delighted that is when the officers smiled at Mitzi — the first stoop in our back. (4: 410)

When the Woolfs reached Bonn, they happened to turn on to a street packed with crowds awaiting the arrival of Hermann Goering. The cheering children lining the street and waving little red flags at them must have bemused the couple as they drove through the crowd.

People gathering in the sunshine —rather forced like school sports. Banners stretched across the street “The Jew is our enemy” “There is no place for Jews in —”. So we whizzed along until we got out of range of the docile hysterical crowd. Our obsequiousness gradually turning to anger. Nerves rather frayed. A sense of stupid mass feeling masked by good temper. (4:443)

They drove on to their hotel over the border in Austria: “The innkeeper is playing cards with his wife. They all want to go away — back to Islington, back to Washington — Oh so lovely, said the waiter, who wants to go on talking.”

At the end of the summer, on September 4, 1935, just 4 years minus a few days before Germany invaded Poland, she writes in her diary upon returning to her London from their house in Sussex, she notices new graffitti:

Writing chalked up all over the walls. “Don’t fight for foreigners. Briton should mind her own business.” Then a circle with a symbol in it. Fascist propaganda, L[eonard] said. [Oswald] Mosley again active. (4: 446)

Fascists and isolationists had become emboldened. Virginia and Leonard were now both certain there would be war.

There’s nothing in Virginia’s diary that we didn’t already know about British perceptions of Nazi Germany. Her record simply reflects the perspective of a well-informed member of the British intelligentsia in the decade before the 2nd world war. Nothing new here. However, the minute parallels with our current political environment bolsters my resolve to take the dangers to our democracy very seriously. The ICE raids, the suspension of habeas corpus, ignoring court rulings, and the openly racist demonization of non US citizens are far more vicious than the danger signs Virginia saw scrawled on London’s walls in 1935. We are closer than many of us think to the bottom of the same slope the Woolfs stared down. They could not see what was coming ahead and so had a hard time imagining it. We, in contrast, know how that story ended in Europe.

Millions of people today know where the rise of the fascist regimes in mid-twentieth-century Europe led. Last Saturday, four to six million people demonstrated their objection to proceeding towards a similar future. That objection rests, in large part, on historical memory. We should all know where the deprivation of civil rights, arbitrary seizure, and manipulation of the vote led in the past, and so it pays to revisit the accounts left by witnesses like Virginia Woolf to remind ourselves of what is at stake. To her great credit, Virginia Woolf understood the stakes and put her pen to work.

Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf, 5 vols. (Granta, 2023). The main differences between the 5 volumes I read back long ago and the 5 new editions are the silent addition of previously suppressed material and the new forwards in each volume by, respectively, Virginia Nicholson, Adam Phillips, Olivia Laing, Margo Jefferson, and Siri Hustveldt.

The Night of the Long Knives, as it was called, refers to the public assassinations between June 30 and July 2 of the leaders of the SA, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party that enabled Hitler and Goering to consolidate power.

This rings so true today: “Meanwhile these brutal bullies go about in hoods & masks, like little boys dressed up, acting this idiotic, meaningless, brutal, bloody, pandemonium.” Thank you for this essay and putting everything in perspective.

Brava!